How Did Romanians First Learn about the New World

- RCI USA

- Mar 29, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 1, 2020

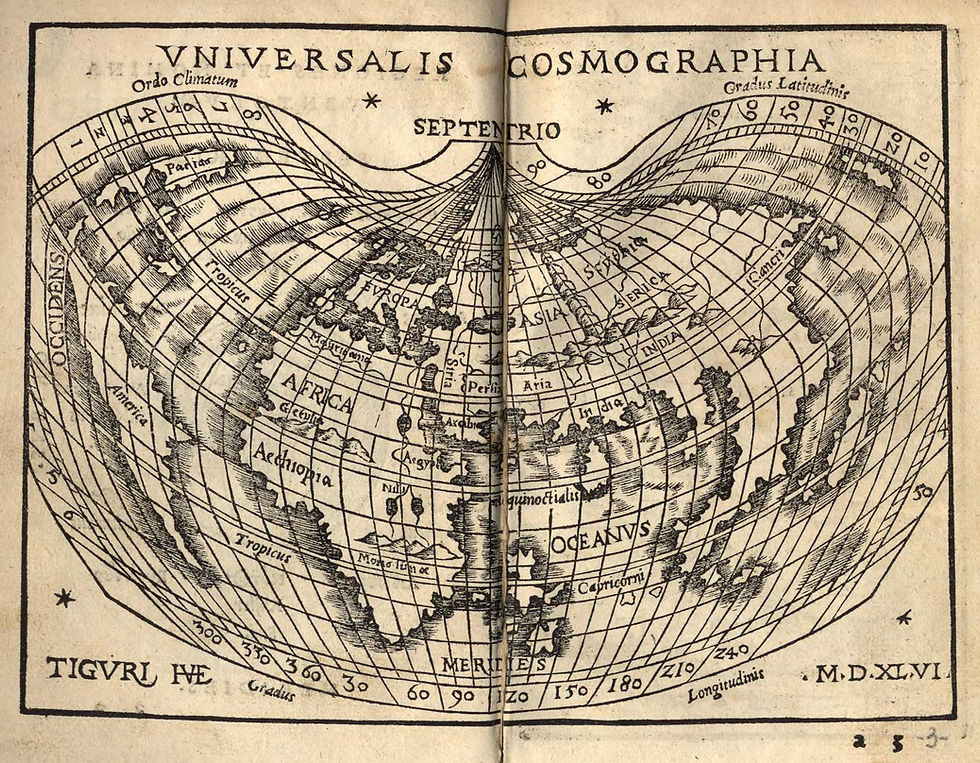

In the Romanian Provinces, Transylvanians are the first to learn about the New World. The earliest information on the amazing exploits of Columbus, Magellan and the conquistadors emerge already in the first decades of the 16th century and even before these novelties begin to circulate in the Kingdom of Hungary and Poland and in the Ottoman and Russian Empires. A humanist of Transylvanian origin, Maximilianus Transylvanus (cca. 1490-1538), publishes in 1523 one of the first, and most influential, works devoted to Magellan’s adventures, in which the New World is seen as “a continent and great and numerous islands full of gold and pearls and other riches.” Another humanist, Nicolaus Olahus (1493-1568), in a speech addressed to Emperor Charles V, glorifies the conquest of America and the conversion of the indigenous peoples. In 1530, in a treatise entitled Rudimenta cosmografica, Johannes Honterus (1498-1549) describes the New World in almost lyrical terms: “Innumerable islands scattered on the infinite ocean, some inhabited by people, some only by the savage jungle of the beasts; islands which mark seaways only seldom taken by sailors. Some of them renown, even famous; other possessing neither glory nor a name from before. Let me bring the tired ships back to our ports.”

The Transylvanians of the 16th century also find out about the New World from the books written by scholars like the German theologian Simon Grynaeus, the Flemish explorer Apolonius Laevinus, and the Italian Jesuit prelate Giovanni Pietro Maffei, which enriched the libraries of the noblemen and the clergy. Like all other Europeans of the time, what they come to discover through these works is a fabulous realm, almost mythical and rich beyond belief, peopled by savages that must be brought under the light of Faith and sometimes deplored for their miseries.

The books on the New World in the Wallachian libraries appear sometime later. Although they may have circulated way before, it is certain that the great erudite Constantin Cantacuzino (cca. 1640-1716) is the owner of several titles related to America, such as the popular atlas of the German Gabriel Bucelin, published in 1672, or the compendium written by the Flemish Jean de Laet and printed in 1633. To Cantacuzino the Romanian Principalities and the New World are granted by fellow contemporaries with the same infuriating ignorance: “The geographers say and tell such stories and falsehoods about these countries [the Romanian ones] but even more so about the Eastern and Western Indies and the places thereof.” A weird notion is expressed by the Wallachian chronicler Radu Popescu (1650-1729) who believes that Christopher Columbus, the discoverer of these new lands, was a French monk in the service of the Spanish king. In Moldova, the great scholar Miron Costin (1633-1691) knows, apparently from Polish sources, that the Americas are in a different time zone because “when it is day at us it is nighttime for them”. The New World is also evoked by the famous savant Dimitrie Cantemir (1673-1723) who equates a detested rival with an American ape.

Towards the end of the 17th century, along with this knowledge Romanians can also taste the products of the Americas. Especially two of them become widely popular: corn, the future basis of our delicious national staple food, polenta, and tobacco – too familiar today, unfortunately, as it was centuries ago.

In the picture: Johannes Honterus, world map, in Rudimenta cosmografica, Zürich, ed. 1548

Reference book: Cernovodeanu, Paul, and Stanciu, Ion, Imaginea Lumii Noi în Țările Române și primele lor relații cu Statele Unite ale Americii până în 1859, Romanian Academy Publishing House, Bucharest, 1977